A slim majority believe that consumers are not prepared to pay higher costs, even though they want sustainable solutions.

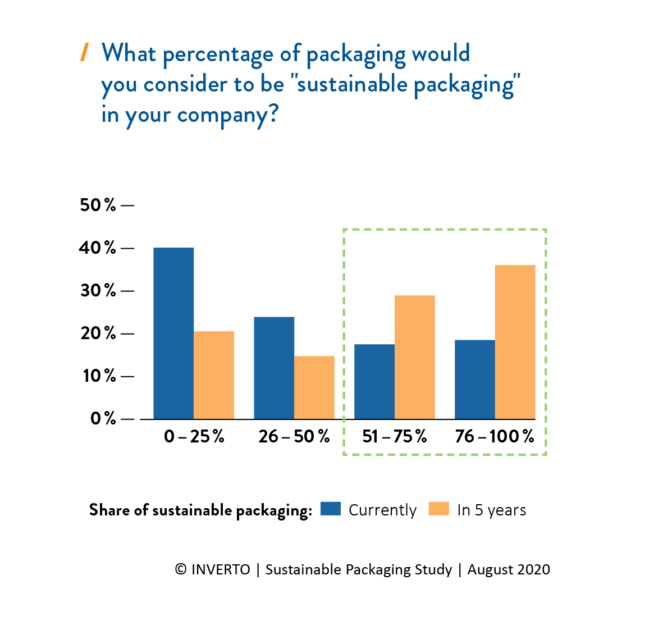

Sustainability in terms of packaging is not a passing trend. The issue is already seen as highly relevant, and this will only increase significantly over the next five years, with pressure coming from politicians as well as consumers. As requirements for material properties increase, targets are also being set for the use of recycled materials. Taxes and financial penalties for using virgin plastics are in the pipeline, while economies of scale mean that manufacturing sustainable packaging will become more affordable over time. There are no short cuts to implementation, so businesses are having to develop and invest in their own strategies to boost sustainability.